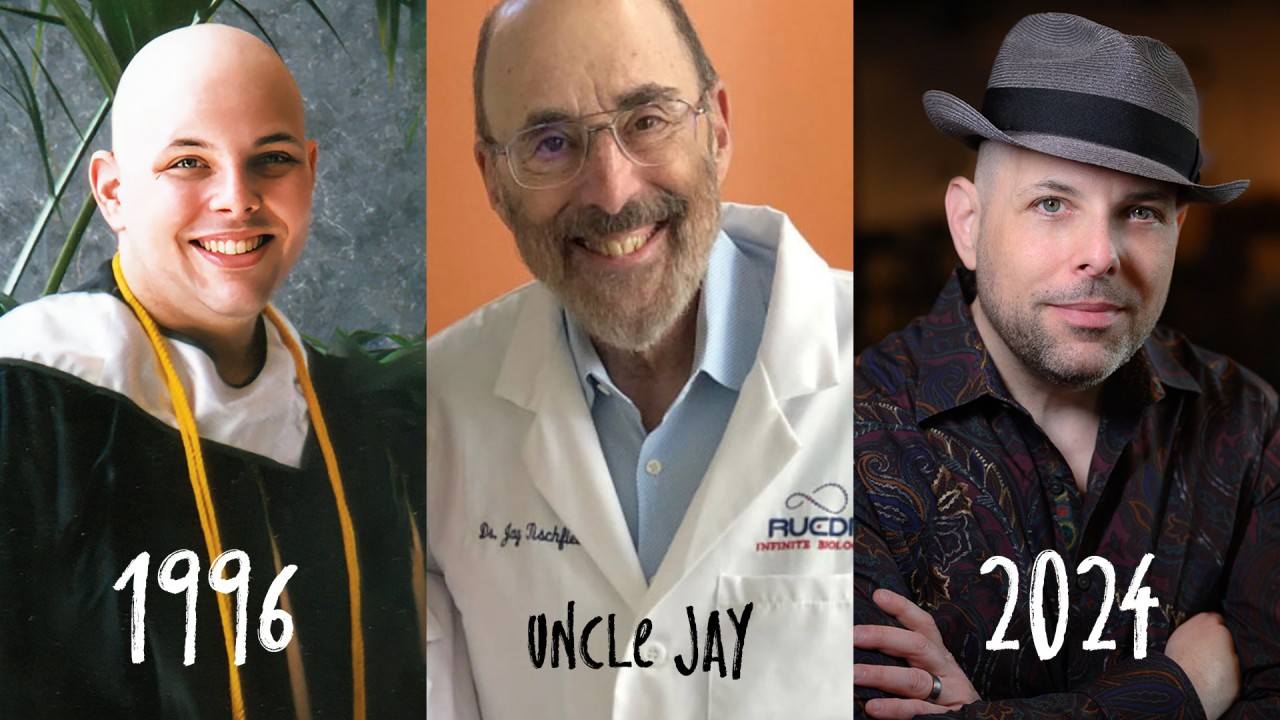

Uncle Jay and Why I Said No to Chemotherapy

I was 21 years old and, under more auspicious circumstances, should have been wrapping up my Senior year at SUNY Binghamton and preparing to embark on my graduate studies at USC Film School to study with the late Jerry Goldsmith and embark on a career as a film composer.

Instead, after an 8-hour craniotomy in January to remove a golf-ball-sized malignant tumor from my cerebellum, between February 15th and April 30th, I endured 33 radiation therapy treatments (5940cGy) to the head, neck, and spine, plus an additional boost of 3300 cGy to the pons within the posterior cranial fossa.

I was a shell of a human being suffering from every possible side effect imaginable, with a quality of life equivalent to that of living inside a volcano with no food, water, shelter, or air. I could not walk, chew, swallow thin liquids, or consume solid foods.

I was impotent, depressed, isolated with burned skin, and skeletal thanks to malnourishment and uncontrollable nausea. I had also lost 110 lbs within the timespan of my treatments and was unrecognizable from the person I was before.

But we weren't done yet.

"Let's talk about chemo," said the doctors.

"First, tell me when I'm going to die," I said.

"Now that you've survived the surgery and radiation, We give you a 50% survival rate over the next five years," they confidently uttered.

"With the chemo, what does that bump the 50% up do?" I asked inquisitively with a hint of sass.

"55%," they proudly avowed with the hubris of a Greek god, "But we need to start immediately."

"I need time to think about it."

Enter Dr. Jay Tischfield, a world-renowned geneticist who has been my father's best friend since they met at Hebrew School in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, in the 1950s.

Jay was my Godfather, a protective surrogate Uncle. Once he found out that chemotherapy was on the table, he immediately contacted Sloan Kettering and demanded to see the protocol. Back in those days, no hospital would share patient data, but Jay knew all the right people to call and, with our permission, of course, got the cocktail recipe.

It was the usual suspects: cyclophosphamide, carboplatin, vincristine, and cisplatin, all blended within a concoction of toxic hell.

Jay—and not my doctors—then brought to my attention the many known acute and long-term side effects of these horrific medications, including two that stood out more prominently:

Vincristine causes near-permanent peripheral neuropathy, and cisplatin causes near-certain ototoxicity. As a professional musician, pianist, and composer, the last thing I wanted to subject myself to was a future with numbness in my fingers and hearing loss.

"Matt, I love you and never thought I'd say these words to you, but you'd rather live a shorter life without these side effects than live longer with them. Don't let them take away your gift."

It was late May 1996. I had just turned 22 and was sitting on the precipice of a life-or-death decision that only I could make.

At my final visit with my doctors, I told them that I would be declining chemotherapy because I'd rather die in 5 years as a pianist than live a full life with these side effects.

"But we're trying to save your life," they exclaimed in a stentorian tenor while rising to their feet in a futile attempt at authoritarianism.

That was my last day as a cancer patient.

If it weren't for my Uncle Jay, I likely would never have fully rehabilitated myself and maintained my craftsmanship, musicianship, owl-like hearing, and identity as a professional pianist.

I am one of the lucky ones. Not everyone has an Uncle Jay in their life, but I have spent the past 25 years of my career attempting to ensure that will no longer be the case for the millions of Americans facing cancer every year.

In Conclusion

In 1996, chemotherapy was not first-line therapy for medulloblastoma. Had it been, I may have had no choice but to risk my career.

Today, those same toxic chemicals are standard-of-care, which means millions of patients are subject to the same ototoxicity, neuropathy, and other acute and long-term side effects as a consequence of their treatment and, perhaps, cure.

My doctors did not seem to care that I was a concert pianist and what was most important to me. They seemed to care more about the protocols. The 1990s were not a time when quality of life was tantamount to quality of care. The word "Survivorship" was barely a decade old and had not translated into best practices.

It is my hope that any cancer patient facing chemotherapy is told in advance of the side effects they will most assuredly face and that doctors take the wishes, priorities, and desires of the patient seriously as part of the jargon known as "shared decision making."

For me, advocacy means helping the "next you" have a much less shitty experience. That was the entire mission of Stupid Cancer, to make youg adult cancer suck a little less.

Patient influence over the "system" is ever-evolving, but one thing is certain beyond any other truth — The real revolution happens when patients are in charge of their own outcomes.

Thank you, Uncle Jay. I love you.

Share your experiences below if this story resonates with you. Did vincristine numb your fingers and toes? Did cisplatin make you deaf? Did your care team tell you in advance? Did you feel in control of what mattered to you?

👇🏻 ⬇️ 👇🏻 ⬇️ 👇🏻 ⬇️ 👇🏻 ⬇️ 👇🏻 ⬇️